Written by Marissa Hendricks, archival processor

The Marlboro School of Music has been a driving force in chamber music in America for over half a century. Every summer it draws applicants from across the globe, vying for an opportunity to spend the next seven weeks playing alongside some of the world’s most talented artists in its idyllic setting in southern Vermont. Marlboro’s influence has intertwined itself into the early music careers of such artists as cellist Yo-Yo Ma, violinist Joshua Bell, and pianist Emanuel Ax. Under the artistic direction of pianist Mitsuko Uchida, also a former participant, the school emphasizes the intensive study of chamber music by bringing together senior artists and talented young musicians to play simply for the joy of playing. This offers a respite to professionals, both young and senior, from strenuous rehearsal and performance schedules. The school was officially founded in 1951 by violinist Adolf Busch, along with his son-in-law, pianist Rudolf Serkin, cellist Herman Busch, flutist Marcel Moyse, pianist and flutist Louis Moyse, and violinist and conductor Blanche Honegger Moyse. Its earliest years are when this philosophy of bringing together junior and senior artists in a relaxed atmosphere initially took root.

Adolf Busch relocated his family to Vermont after immigrating from Europe at the outbreak of The Second World War and the Moyse Trio had also fled Europe and came to Vermont after living in exile in Argentina. In 1950 the founder of Marlboro College, Walter Hendricks, approached them about conducting a summer music program for the nascent college. That first year had few participants and little planning, with a number of unimpressed participants, mostly string players, leaving shortly after their arrival, but a seed was planted nonetheless. The following year, the Marlboro School of Music became its own separate institution from the college and held its first official summer school and festival with over fifty participants.

In June of 1952, however, Busch suddenly passed away, leaving his son-in-law, Rudolf Serkin, in charge of running the school. Marlboro was Busch’s vision; a concept of which he had dreamed for many years and yet no sooner did the school get underway than he had already become a ghost of its origins. Serkin committed himself to preserving his father-in-law’s philosophy and Marlboro quickly became a monument to his memory. Now with Serkin gone for nearly twenty-five years, Marlboro has become a monument to him as well as Busch.

The Kislak Center acquired the Marlboro Music School and Festival Records in January 2013. Comprising 227 containers, the collection documents the entire history of the school and festival through administrative documents, printed ephemera, photographs, and audio-visual materials, from its origins in the early 1950s through the present day. With such a dizzying amount of material, the ghosts of Busch and Serkin can all too easily become buried under so much paper.

How do these ghosts emerge from the collection? If Marlboro was Busch’s vision even before it was Serkin’s, where are there glimpses of him that represent the preservation of his spirit? In her book The Allure of the Archives, Arlette Farge explains that “the archive lays things bare, and in a few crowded lines you can find not only the inaccessible but also the living” (8). What does this mean for an individual who was already an immaterial presence by the time most of the archive’s earliest documents were being produced? Serkin was the torchbearer of Marlboro’s mission, but he too is a ghost in the collection. Busch and Serkin are as immaterial as the music they produced; enduring in memory but lacking in physicality. The archive is where they can regain their voices through documents that speak to their enduring influence on Marlboro.

In its earliest years and in accordance with Busch’s original plans, the school still welcomed applications from amateur musicians and there is correspondence in the collection that reflects this dynamic. Often parents of very young amateur musicians would write to inquire about attending the school or arranging private lessons on behalf of their son or daughter. In the 1960s Serkin formed an auditors program that covered tuition costs for several underprivileged youths to attend the school each year and he often paid the expenses out of his own pocket. The letters exchanged regarding the auditors program expressed Serkin’s earnest desire to keep the program running despite the financial difficulties. In fact, much of the early applicant correspondence contains pleading requests for financial assistance and inquiries about scholarships from young musicians who want to attend, but simply can’t afford it. Application forms asked for the occupations of their parents and all too often the applicants came from humble beginnings, with their mother described as a “housewife” and their father as a laborer of one kind or another. Household incomes were listed and it often became immediately clear why applicants simply weren’t able to pull together an extra $50 to cover the remaining cost of tuition themselves.

Busch and Serkin themselves were both uncomfortably well-acquainted with poverty. Busch’s father was a cabinet-maker and luthier who had broken out of his peasant caste out of sheer tenacity and impulsiveness; he’d run away to Hamburg as a teenager to study the violin. Busch’s biographer Tully Potter describes the household as a poor one, noting that “Adolf never had a winter coat as a child” (39). Serkin too endured poverty during his childhood, particularly during his family’s time living in Vienna in the years leading up to his meeting with Adolf Busch. Upon agreeing to take him under his wing, Busch instructed his maid that when the young Serkin arrived at his house in Berlin the first thing she was to do was to point him in the direction of the bathtub (287). It is no wonder that Serkin so frequently paid out of his own pocket to cover the cost of running the school in those first years and why one of the cornerstones of the school was that financial status should not be a factor in determining participation in the school.

Another hallmark of Marlboro’s approach to musicianship that hearkens back to its original philosophy is its elaborate system of determining the season’s repertoire. At the beginning of each season, participants excitedly filled out forms in which they requested the works they would most like to study that summer. This morphed into weekly and daily rehearsal schedules and detailed tabulations of which works were studied and which artists had played together. The collection contains many years of these request forms and incredibly detailed schedules, underscoring the attitude of equality that is integral to Marlboro. Junior artists have just as much say as senior artists and no one voice is louder than the other. Serkin often referred to Marlboro as a “republic of equals” and this democratic system of planning the season’s course of study epitomizes that sentiment.

Perhaps one of the most enjoyable aspects of this collection has been the legacy of Serkin’s and Busch’s wry sense of humor. Both known for their tendency to delight in practical jokes, this is a phenomenon that has pervaded Marlboro’s culture for many decades, with the most well-known tradition being the napkin ball fights that punctuated the end of evening meals in the dining hall at Marlboro, with Serkin typically being the instigator, throwing the first napkin ball with great ceremony. Busch too had a wickedly playful side– Potter retells an occasion when Busch, “thought it hilarious that while playing Bach’s A minor solo Sonata, he moved into the G minor one by mistake [and] found his way back again without anyone in the audience apparently noticing” (585). On another occasion, Busch noticed a young student carefully watching the movements of his left hand as he played and so Busch contorted his left hand into the most bizarre fingerings he could manage without ever once compromising the quality of his music (585).

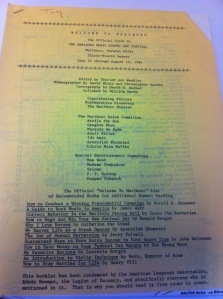

That distinctive humor has woven itself into the archive’s records in examples such as an odd piece of handwritten music wittily titled “Baacarole”– a ditty honoring the campus’s resident flock of sheep– playfully composed by the school’s administrator with accompanying lyrics by their formidable wordsmith of a librarian. The many recollections of past participants also contain gems of Marlboro humor, many of the standard practical joke variety: filling out a signup sheet for an upcoming performance with fake names, only to learn that it was sent off to the printers; wheeling a fellow participant’s car inside a campus building under cover of night; or even the tongue-in-cheek voice of the “Welcome to Marlboro” information packet, with contributions attributed to figures such as the Ayatollah Khomeini and Luke Skywalker. All of these pranks echo the often playful spirits of Busch and Serkin.

The beauty of this collection can be found in some of its most unassuming papers, whether it is the earliest letters from earnest young applicants, typed on highly acidic and brittle paper, or the thickly curled sheafs of scheduling files, painstakingly assembled to ensure that all participants have a say and that Marlboro therefore remains a republic of equals. “Archival discoveries are a manna that fully justify their name: sources, as refreshing as wellsprings” (Farge, 8). These gems of the archives are what link us to the immaterial aspects of a collection. Beyond the papers and even beyond the music are the philosophies and attitudes that constitute the spirit of Marlboro. It remains a monument to the artistic dreams of both Busch and Serkin through its collaborative, collegial environment and its commitment to making music for the sheer joy of it.

Works Consulted

Busch, Adolf. Adolf Busch: Letters, Pictures, Memories. Walpole, N.H. : Arts & Letters Press, 1991. Print.

Farge, Arlette. The Allure of the Archives. New Haven : Yale University Press, 2013. Print.

Lehmann, Stephen and Marion Faber. Rudolf Serkin: A Life. New York : Oxford University Press, 2003. Print.

Potter, Tully. Adolf Busch: The Life of an Honest Musician. [London] : Toccata, 2010. Print.

2 responses to “Processing the Immaterial, Touching the Real: Ghosthunting in the Marlboro Music School and Festival Records”

[…] ← Previous […]

[…] of practical jokes, crude humor, and other forms of childish fun, as Marissa has pointed out in her blog post on the Marlboro Music School and Festival records. According to some, he initiated the now famous […]