Written by Abby Lang, Rare Book Cataloger

While cataloging a volume of nineteenth century anthropologic and ethnographic pamphlets on the Indians of North America, this pamphlet jumped out with its typographically festive message of cultural imperialism and racialization: Velasquez, Pedro. Memoir of an eventful expedition in Central America : resulting in the discovery of the idolatrous city of Iximaya, in an unexplored region, and the possession of two remarkable Aztec children, descendants and specimens of the sacerdotal caste (now nearly extinct) of the ancient Aztec founders of the ruined temples of that country / described by John L. Stevens, Esq., and other travellers ; translated from the Spanish of Pedro Velasquez, of San Salvador.

Velasquez, Pedro. Memoir of an eventful expedition in Central America : resulting in the discovery of the idolatrous city of Iximaya, in an unexplored region, and the possession of two remarkable Aztec children, descendants and specimens of the sacerdotal caste (now nearly extinct) of the ancient Aztec founders of the ruined temples of that country / described by John L. Stevens, Esq., and other travellers ; translated from the Spanish of Pedro Velasquez, of San Salvador.

New York : E.F. Applegate …, 1850. 35, [1] p. : ill. ; 22 cm.

Cataloging this pamphlet turned up an extremely sad history involving the kidnapping of two children from El Salvador, nineteenth century conceptions of race and disability in America and Europe, and P. T. Barnum and the American circus freak show. The pamphlet Memoir of an eventful expedition in Central America helps tell the story of the construction of racial and ethnic others during the period of the birth of American anthropology.

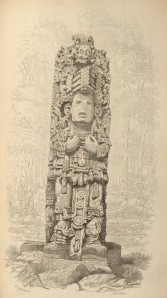

The “idolatrous city of Iximaya”, as well as the author of the pamphlet, Pedro Velasquez, are both imaginary. The inspiration for the Maya city and this fictitious memoir was John Lloyd Stephens’ 1841 seminal travel account Incidents of travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatan, illustrated by Frederick Catherwood. Stephens was a travel writer from New York City, who, along with Catherwood, spent the years of 1839 to 1843 traveling in Mexico and Central America. Stephens provides grandiloquent descriptions of ancient Maya ruins and the indigenous communities they encountered, and accompanied by Catherwood’s precise architectural engravings, the text was an early introduction to the ruins of Maya cities for a mesmerized North American and European audience.

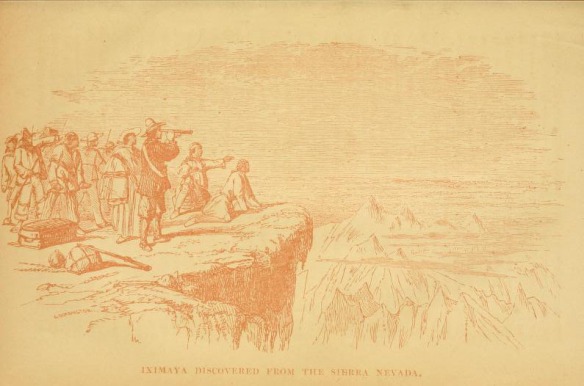

As told in Incidents of travel in Central America, on their way to the ruins of Palenque in southern Mexico, Stephens and Catherwood hear a story from an “old padre” of an ancient city “occupied by Candones, or unbaptized Indians, who live as their fathers did, acknowledging no submission to the Spaniards, and the government of Central America does not pretend to exercise any control over them.” This city could allegedly be seen from a distance from the top of the neighboring sierra, but no white man had ever set forth within the city, as the inhabitants “are aware that a race of strangers has conquered the whole country around, and murder any white man who attempts to enter their territory” (Stephens 195; vol. 2).

Stephens and Catherwood couldn’t deviate from their itinerary and take the time to reach the city, or even to climb the highest ridge of the sierra to see the mysterious city below. They had heard of another explorer who did reach the top of the ridge, only to find the city obscured by cloud cover, and the old padre had seen it from afar, so their interests were definitely piqued: “the interest awakened in us was the most thrilling I ever experienced. One look at that city was worth ten-years of an every-day life” (Stephens 196; vol. 2).

Stephens speculated that “Two young men of good constitution, and who could afford to spend five years, might succeed” in reaching the city (197; vol. 2).

This is where our pamphlet Memoir of an eventful expedition in Central America picks up the story, with the introduction of the very two men equipped to reach “Iximaya”, Mr. Huertis and Mr. Hammond. This fictional narrative follows the two men on their travels from Belize to the mythic Maya city (supposedly located in Chiapas), meeting Sr. Pedro Velasquez, of San Salvador, along the way. Velasquez acts as their guide and also keeps a manuscript journal of the journey which is supposedly translated into Memoir of an eventful expedition in Central America.

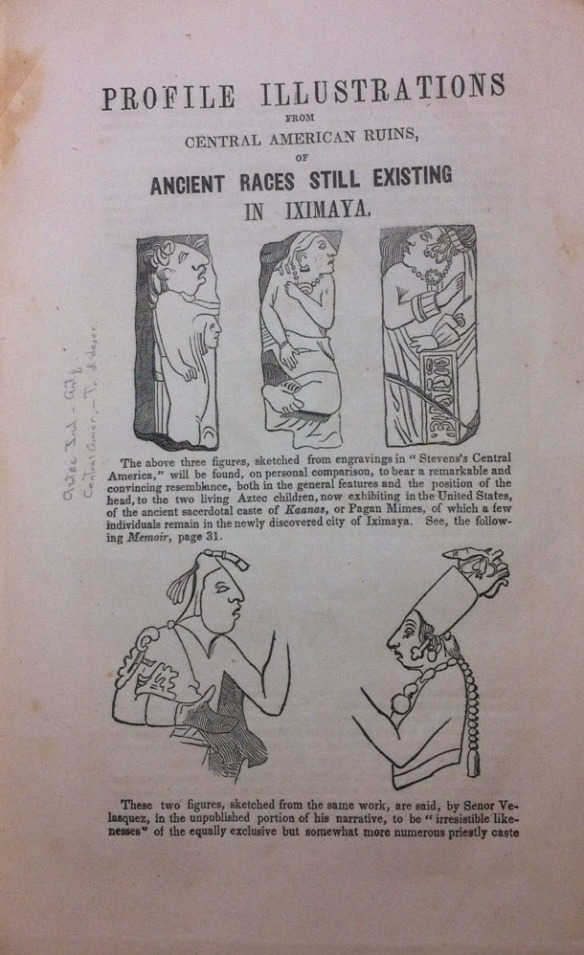

The pamphlet describes the discovery of Iximaya, as well as of two small children kept within the city, the “surviving remnant of an ancient and singular order of priesthood called Kaanas, which … had accompanied the first migration of this people from the Assyrian plains” (Velasquez 31). The Iximayans held the remaining members of this race in veneration, as “living specimens of an antique race so nearly extinct” (31). The legend of the Mayas of Iximaya killing all white intruders was upheld in this account, and only Velasquez leaves alive, kidnapping the Kaana sister and brother and returning to El Salvador.

Velasquez describes the children as “diminutive in stature, and imbecile in intellect”, but also as “the greatest ethnological curiosities in living form … as specimens of an absolutely unique and nearly extinct race of mankind that they claim the attention of Physiologists and all men of science” (35). According to Memoir of an eventful expedition in Central America, Velasquez sends the children, at the ages of eight and ten, to the United States to exhibit them as specimens of this almost lost race (35).

The two children became known to the world as Maximo and Bartola Velasquez, or the Aztec Children, and performed in circus freak shows for four-decades. This pamphlet was published, possibly for P.T. Barnum (Evans 85), as a promotional piece for exhibits of the Aztec Children, to arouse curiosity in these living specimens from ancient Mesoamerica.

The stories of their discovery at Iximaya and their race are fictitious—in truth, the children suffered from microcephaly, a neurodevelopmental disorder that results in reduced head-size and impaired intellectual development, and possibly dwarfism. They were found in the 1840’s in a small village in the state of San Miguel, El Salvador by a Spanish trader named Ramón Selva, who promised their parents to bring them to the United States for treatment of their condition, but instead sold them to a promoter named Morris (Bogdan 127). The physical attributes of their disorder were exploited in order to bill them as the “Remarkable Aztec Children, descendants and specimens of the Sacerdotal Caste (now nearly extinct) of the ancient Aztec founders of the ruined temples of that country.” Morris and others compared their look as strikingly similar to engravings in Stephens’ Incidents of travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatan of ancient Mayas depicted in stone within various Maya ruins. It is unclear why these children were referred to “Aztec” rather than Maya, but presumably “Aztec” was being used to mean pro-Colombian Mexican in general, as was common in the nineteenth century.

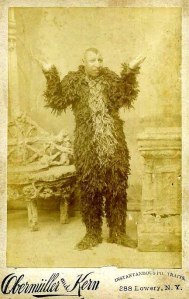

Dressed in pseudo-Aztec costumes, the Aztec Children first appeared in the U.S. in the early 1850’s to an electrified American public and medical community. The mayor of Boston attended and promoted an early appearance of the children there, they were brought before the Boston Society of Natural History, and papers about them appeared in subsequent years in medical journals such as The American Journal of the Medical Sciences and The Lancet. Members of the Senate and House of Representatives met with Maximo and Bartola, and they were invited to the White House to meet President Millard Fillmore. In 1853 they were taken to England by Morris. Billed there as the “Aztec Lilliputians,” they were exhibited at the Ethnological Society and met the Royal Family at Buckingham Palace before continuing a tour of Europe and meeting with other royal families (Bogdan 131).

When the Aztec Children returned from Europe they were taken on by P.T. Barnum, first as an exhibit at the American Museum in New York City, and eventually touring with the Barnum and Bailey Circus until around 1890 (Bogdan 132).

Maximo and Bartola were victims of American and British post-colonial attitudes towards Latin America—the removal of Spain in the 1820’s ushered in a time of increased exploration and study of the region and the ruins of pre-Columbian times. European scholars attempted to solve the mysteries of the creation of the ancient cities ignoring the possibility that the indigenous people of Latin America could be the direct descendants of the builders of these civilizations. R. Tripp Evans describes the climate, in Romancing the Maya: Mexican Antiquity in the American Imagination:

Attempting to reconcile the co-existence of Pre-Columbian civilization with ancient cultures of the Old World, authors either implicitly or explicitly linked the two, discrediting ethnic continuity in Latin America as well as accounts of parallel creation. Proposing various theories of trans-Atlantic migration, early writers on Mexican antiquities supported the commonality of man’s descent from the Old World—an assistance that justified Mexico’s cultural colonization in the wake of Spain’s departure (11).

This refusal to recognize the indigenous people as independent historical groups with connections to the historical sites on their land allowed explorers to feel entitled to Latin America’s cultural artifacts.

Stephens, on the other hand, believed the ancient structures in Latin America to be unique to the New World (therefore subject to U.S. claims) but at the start believed that the builders were of a race now extinct. He later acknowledged a connection between the ancient Mayas and the present-day population in his writings, but judged the race to be in a vastly inferior state than it had been when the cities were created (Evans 66).

Despite having made this connection, Stephens still attempted to purchase all of the Maya sites he visited. He successfully purchased the ruins of Copán, Honduras for fifty dollars and described a plan to dismantle the site and transport it to New York City, where he would “found an institution to be the nucleus of a great national museum of American Antiquities” (Stephens 128 ; 115; vol. 1). When he was refused purchase of other sites, he stole objects from the sites instead. Stephens’ initial reluctance to credit the present indigenous people as having a direct connection with the ancient Mayas, and his belief in the degradation of the race explains why the story of the “living city… occupied by Indians, precisely in the same state as before the discovery of America” was so thrilling for him (195; vol. 2). The story of Maximo and Bartola, cordoned away in inner Iximaya, fascinated the public because they represented a “lost race” and explained the origin of the builders of the ancient monuments to be descendants of Assyrians.

Between the decades of the 1820’s and 1850’s, scores of pre-Columbian artifacts were removed from Latin America, and this cultural theft included human trafficking as well, as shown in the story of Maximo and Bartola. The Aztec children were not lone freaks on display for American and European audiences, but part of a greater trend in the collection and display of human and material artifacts in museums, circuses, and freak shows.

In Maximo and Bartola, Barnum was fulfilling the public’s and the scientific community’s desire to view and fetishize racial others and human abnormalities, and the growing fields of anthropology, archeology, and ethnology fueled this scientific racism. As Bluford Adams writes in E. Pluribis Barnum: The Great Showman & the Making of U.S. Popular Culture, “the circus’s search for the anatomical markers that would signify racial difference came amid an unprecedented effort on the part of Darwinian ethnologists to measure and systemize the physical differences among the races” (183).

In 1884, Barnum opened the Ethnological Congress of the Barnum and London Circus, which featured people of various ethnicities from around the world as specimens for a mostly white audience to view, such as “Zulu Warriors, Princess, and Child”, “Band of Nubians from Soudan”, “Genuine Hindoo Nautch Dancers” and of course, the “Aztecs of Ancient Mexico” (Adams 176). During and after the Aztec Children’s rise to fame, other people with microcephaly were being exhibited as Aztecs in circuses, copying the look and myths of Maximo and Bartola (Bogdan 132). People with microcephaly began to be referred to as pinheads, and other famous acts include Tik Tak the Aztec Pinhead; Zip, also referred to as “What Is It?”; and Schlitzie the Pinhead, who became famous for his appearance in the classic 1932 horror film Freaks. Robert D. Aguirre describes racial exhibitions in the mid-to-late nineteenth century:

Freak shows depended on a supply of curiosities from abroad, which in turn provided racial theorists with new ‘specimens’ to analyze. Racial characterizations were then funneled back into the materials purveyed by freak show promoters, lending them an air of respectability and further securing scientific to mass culture. Ethnology gained access to rare specimen, and racial ideology was disseminated to a broad public (44).

The Aztec Children were not only sold into a life of sideshow performance, but they were also subjected to medical tests and ethnological examinations and cranial measurements in order to study their racial traits. The scientific community eventually discredited the pamphlet’s and Barnum’s assertion of their “pure race” (Aguirre 56). Despite their racial status lowered to that of mestizos, they continued to draw crowds at Barnum’s circus, until fading into obscurity near the turn of the century.

Memoir of an eventful expedition in Central America is part of the Berendt-Brinton Linguistic Collection, manuscripts and books mainly on Mesoamerican linguistics collected in Latin America by the explorer and physician C. Hermann Berendt and later acquired by the archaeologist and ethnologist Daniel Garrison Brinton. To view other items with this collection, search for the Berendt-Brinton Linguistic Collection in the Franklin catalog.

Works Cited

Adams, Bluford. E. Pluribis Barnum: The Great Showman & the Making of U.S. Popular Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997. Print.

Aguirre, Robert D. “Exhibiting Degeneracy: The Aztec Children and the Ruins of Race.” Victorian Review 29.2 (2003): pp. 40-63. Web. 26 Mar. 2014.

Bogdan, Robert. Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1988. Print.

Evans, R. Tripp. Romancing the Maya: Mexican Antiquity in the American Imagination, 1820-1915. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004. Print.

Stephens, John L. Incidents of travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatan. London: John Murray, 1841. Web. 26 Mar. 2014.

Velasquez, Pedro. Memoir of an eventful expedition in Central America : resulting in the discovery of the idolatrous city of Iximaya, in an unexplored region, and the possession of two remarkable Aztec children, descendants and specimens of the sacerdotal caste (now nearly extinct) of the ancient Aztec founders of the ruined temples of that country / described by John L. Stevens, Esq., and other travellers ; translated from the Spanish of Pedro Velasquez, of San Salvador. New York : E.F. Applegate, 1850. Print.

Abby Lang is a bibliographic assistant in the Special Collections Processing Center at the University of Pennsylvania. She is a graduate of the Master of Library and Information Science program at Drexel University.

2 responses to “Maximo and Bartola and the myth of Iximaya”

[…] Maximo and Bartola, the microcephalic children from San Salvador, received full treatment in a nice blog post from a few months ago. I like to consider that Dickinson probably saw this daguerreotype in […]

Reblogged this on Bibliodeviancy.