Lions are primarily pursuit predators, although “ambush behaviour has been observed … mainly during daylight when stalking prey is more difficult” (“Predatory Behaviour”). I presume this accounts for the way three more books from the press of sixteenth-century Swiss printer Nikolas Brylinger—he of the clock-watching lions—leapt out at me from the Kislak Center’s holdings after I had finished my post on his career. Two of his textbooks were hiding under Dewey Decimal call numbers: a 1553 edition of Thomas Linacre’s De Emendata Structura Latini Sermonis Libri VI (475.3 L63a) and a 1545 edition of Theodōros Gazēs’s introductory Greek grammar (485 G259), the latter presented to the Penn Libraries by University alumnus, faculty member, and prolific donor Dr. Charles Walts Burr (1861-1944).¹ The third volume lurking in the stacks is a 1542 edition of humanist Agostino Steuco‘s De Perenni Philosophia Libri X (B785.S8 A3 1542), an attempt to reconcile classical philosophy with Christian doctrine and one of three titles Brylinger printed with Sebastian Franck. This book contains two different versions of Brylinger’s device, one on the title leaf (shown above) and one on the verso of the last printed leaf; they are also the earliest examples of his lion logo in the Kislak Center’s holdings, predating the one in Brylinger’s Xenophontis Philosophi ac Historici Excellentissimi Opera (1545) I identified in my previous post. Adding to its interest, the Kislak Center’s copy of De Perenni Philosophia came to Penn by a decidedly circuitous route: it contains marks of provenance identifying six former owners across three centuries, all of them traceable.

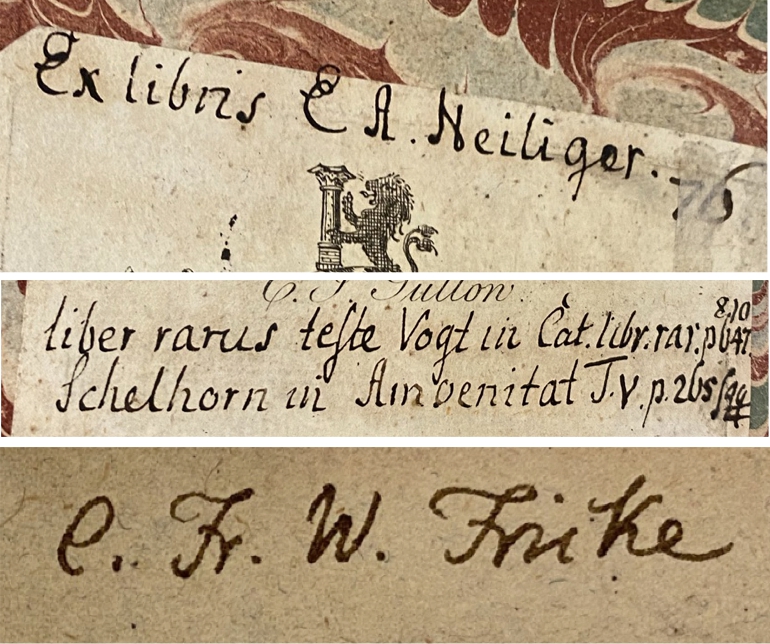

Let’s begin with C.J. Sullow, named in an eighteenth-century armorial bookplate affixed to the book’s front pastedown and an inscription dated 1756 on the verso of its front free endpaper. Christian Johann (or John) Sullow (sometimes spelled Sillow or Süllow) was the son of Caspar Süllow (ca. 1687-1750), a clerk in the Deutsche Kanzlei, the London office of the Hanoverian government, from 1731-1749 (Richter-Uhlig 169). In 1735 Caspar accompanied the household of King George II on one of its periodic trips to Hanover and while there married Ilsa Mehlbaums at the Schlosskirche on 14 September (ibid.; “Heirat”). Their son C.J. Sullow was born no later than 1739 in London, a fact he proudly advertised throughout his life, signing himself “of London,” “aus London,” and “Londinensis.” After his father’s death C.J. Sullow became the ward of Wilhelm Osterheide (also spelled Osterheyde and Osterheit; d. 1768), Caspar Süllow’s nephew and himself a minor functionary at the Deutsche Kanzlei from 1751 onward (Richter-Uhlig 169). Osterheide dutifully fitted his young cousin for a professional career, sending him to the venerable Academia Julia of Helmstedt, Germany, in 1754 to study law.

Sullow matriculated at Helmstedt on 21 June and immediately began making friends. Preserved from his time there is an epithalamium for the “Henning and Fischer wedding celebrations” [Henningischen und Fischerschen Hochzeitsfeste]—probably the nuptials of theology student Johann Carl Wilhelm Fischer of Nordhausen on 24 September 1754—which Sullow wrote with another recent matriculant, C.J.H [Christian Julius Heizo] Bauer (1729-1789) of Wunstorf (Fritzsche 98, note 4).² Two years later, however, Sullow transferred from stodgy Helmstedt to the up-and-coming Georg August University of Göttingen, entering its law school on 5 May 1756. The Georgia Augusta, as it was familiarly known, was notable at the time for its attractiveness to foreign students:

In addition to the British there were Swedish, Russian, French, Italian, and even Argentinian students in Göttingen. During the early years of the University’s existence the largest contingent of Göttingen’s foreign students came from Sweden. After 1750 an increasing number of students came from Great Britain, and by the 1770’s the British represented the largest segment of foreign students in Göttingen with as many as fifteen students in a given year. (Stewart 25)

C.J. Sullow was one of “thirty-six British [who] matriculated during the years 1750-1756,” an early peak for U.K. registrants (ibid.). Unlike many of his countrymen, “who herd together, and by always talking their own tongue, never acquire a fluency in that of the country” to the irritation of one contemporary witness (quoted in Stewart 25), Sullow did not confine his social life to the expatriate community. His autograph appears in the Stammbücher (albums) of three other continental students from 1756-1758: Germans Georg Wilhelm Wienecke of Lüneburg and Petrus Simon of Hamburg, and Hungarian Gábor Perlaki, for whom Sullow professed his affection in English: “The fountains into blood return, if I inconstant prove, / the fish shall in the Ocean burn if I cease thee to love / Beloved friend! / When this you see / remember me / your most humble servant / CJ Sullow of London / Student of the Laws” (“Albumtulajdonos: Perlaki, Gábor”). Sullow was also a member of Göttingen’s chapter of the Studentenorden [student secret society] Loge Amicitia et Concordia im Orden der Unzertrennlichen, which he probably first joined at Helmstedt. Casting a watchful eye over the society in 1758, the authorities of the Academia Julia opined “that ‘Mr. Silo’ brought it from Göttingen to Helmstedt” [dass “Herr Silo” ihn von Göttingen nach Helmstedt gebracht habe], while those of the Georgia Augusta countered “that it had been transplanted from Helmstedt to Göttingen” [dass er von Helmstedt nach Göttingen verpflanzt worden sei] since society members “C.J. Sillow (Sullow) … J[ohann]. W[ilhelm]. Jansen … [and] S.J.S. Schulze³ … transferred from Helmstedt to Göttingen” in 1756-1757 [C.J. Sillow (Sullow) … J.W. Jansen … [und] S.J.S. Schulze … gingen also von Helmstedt nach Göttingen] (Richter 64). Regardless of the relative precedence of their chapters, however, both universities recognized C.J. Sullow as a prominent member of the Loge Amicitia et Concordia, standing out among those confreres “who went from Helmstedt to Göttingen and made themselves known there only through the use of a sign peculiar to the society” [das von Helmstedt nach Göttingen ging und sich erst dort durch ein Erkennungszeichen zum Orden bekannt hat] (ibid.).

Not that Sullow failed to make use of the society’s Erkennungszeichen himself. Such things were de rigueur for the clubbable young men steeped in “the sentimental culture of friendship” cultivated by eighteenth-century fraternal organizations where “ritual behavior … add[ed] a symbolical level to [friends’] interaction and infus[ed] it with metaphysical meaning” (Kagel 215). Thirty years later Sullow could still memorialize his membership in the Loge Amicitia et Concordia with elements of “a cipher which was used for internal correspondence between lodges of the same order and was only known to individual, particularly reliable lodge brothers who already belonged to a higher lodge grade” [einer Geheimschrift, die dem internen Schriftverkehr zwischen den Logen desselben Ordens diente und nur einzelnen, besonders zuverlässigen Logenbrüdern, die bereits einem höheren Logengrad angehörten, bekannt war] (Richter 65). “Your Friend and Servant C. John Sullow of London” appended to his 16 April 1783 autograph in the album of naturalist Carl Sievers a series of abbreviations—”V. a H. L’E :/:. A. e. C” (Eckhardt 215, plate 4)—of which the second-to-last (“:/:”) is “a common Amicist symbol” [ein allgemeines Amicisten-Zeichen] and the last (“A. e. C”) stands for Amicitia et Concordia, “the oldest … of the lodges’ identification marks being used in Helmstedt album entries” in the 1750s [Von den … bei Helmstedter Stammbuch-Eintragungen in Übung kommenden Erkennungszeichen der Logen … das älteste] (Richter 67, 64). Below these abbreviations Süllow has drawn a hexagram with a dot in the center, “[a] design that appears to be a Masonic symbol” (Eckhardt 215). The Studentenorden of the mid-eighteenth century took inspiration both structurally and in practice from Freemasonry (Hardtwig 242ff), so it is not surprising that the convivial C.J. Sullow graduated from the Loge Amicitia et Concordia to a Masonic lodge. By 1788 he was Meister vom Stuhl (Worshipful Master) of Zur königlichen Eiche in Hameln, Germany, and the 1796 auction catalog of his library lists a number of texts on Freemasonry in both English—such as Anderson and Entinck’s Constitutions of the Antient and Honourable Fraternity of Free and Accepted Masons (1767; Verzeichniss 5) and Preston’s Illustrations of Masonry (1781; Verzeichniss 24)—and German—such as Feddersen’s Dreymal drey Reden über die Uebereinstimmung der Freymäurerey mit der Religion (1778; Verzeichniss 22), von Lestwitz’s Meine Gedanken über die Zwey Kleine Freymäurerische Schrifte An meine Brüder und An unsere Brüder (1780; Verzeichniss 23) and the periodicals Almanach für Freymaurer (Verzeichniss 40) and Ephemeriden der Gesammten Freimaurerei in Deutschland (Verzeichniss 22).

Sullow’s library eventually encompassed at least six hundred titles on topics ranging from Masonry to medicine and, like his social life, flourished during his university career. No doubt it was then that he acquired law textbooks such as Helmstedt professor Johann Konrad Sigismund Topp’s Explicatio Indicis Juris Civilis Privati prae-vel Recursorii (1756; Verzeichniss 3) and Göttingen professor Justus Claproth’s Kurze Vorstellung von dem Lauf des Processes (1757; Verzeichniss 12); he may also have picked up some lighter works at this time, such as the songbook Lieder mit Melodien (1758; Verzeichniss 18), a Sammlung Scherzhafter Erzehlungen [Collection of Amusing Tales] (1756; Verzeichniss 40), and Die Lustige und Wohl-Gemuthete Jungfern-Schule (1747; Verzeichniss 14), which contains what Hugo Hayn’s Bibliotheca Germanorum Erotica describes as “rather harmless love stories” [Zieml[ich] harmlose Liebesgeschichten] (140). In 1756 Sullow attended the auction of the library of the late chancellor of the Georgia Augusta, professor of divinity Johann Lorenz von Mosheim (1694?-1755), and purchased at least two items: a sixteenth-century German manuscript prayer book (Germanisches Nationalmuseum Hs. 198448) illustrated by Nikolaus Glockendon for a member of the Kiefhaber family of Nuremberg (Grebe 100) and the Kislak Center’s copy of De Perenni Philosophia. Sullow made a note of his purchase in both volumes (see images above); the one in De Perenni Philosophia reports not only the price he paid for the book itself—”ex auct. Moshemiana Gottingae comparatum 1 [Reichstaler]. 9 [Gutegroschen]“—but also what he paid for its binding—”ligatura 12 [Gutegroschen]“. Although Sullow acquired some other manuscripts, such as fourteenth-century copies of the Bible (SUB Göttingen MS Theol. 2) and of the poem Cursor Mundi (SUB Göttingen MS Theol. 107r) and a unique fifteenth-century manuscript of Thomas Castleford’s Chronicle (SUB Göttingen MS 2o Cod. hist. 740 Cim.), as well as a rather larger number of early printed books, including William Lyndwood‘s Constitutiones Provinciales Ecclesiae Anglicae (1496; Verzeichniss 39) and Michael Servetus‘s controversial (and now extremely rare) Christianismi Restitutio (1553; Verzeichniss 32), most of his acquisitions appear to have been of contemporary rather than antiquarian interest: three-quarters of the items Sullow’s heirs offered for auction in 1796 were eighteenth-century imprints, almost half of which were published between 1740 and 1769.

After completing his studies at Göttingen, C.J. Sullow returned to London as a candidatus juris and put his newly minted legal skills to use by filing a complaint against his guardian Wilhelm Osterheide. “I claim from Mr. Osterheyde £1570,” he wrote on on 17 April 1760, “which money he now pretends he does not have, although the same man recently used £200 which he already promised to transfer to me” [Es ist meine Forderung an H. Osterheyde 1570£ der er nun vorgiebt, dass solches Geld nicht habe, ohnerachtet, selbiger noch kürtzlich 200£ die er mir schon zu transferiren versprochen eingesezt hat] (“Rechtskandidat Christian Johann Süllow” 3). Osterheide had managed his cousin’s inheritance for the last decade; references to the plaintiff as Osterheide’s “former ward” (gewesene Pupille) in the case documents indicate that by the spring of 1760 Sullow had reached the age of majority (21 in Great Britain; 25 in Hanover). He alleged that Osterheide was enriching himself at Sullow’s expense and that Osterheide’s claims of financial hardship were exaggerated: “But to some of my good friends it seemed as if he had actually made money in one business or another, and deliberately wanted to reduce me to poverty. He still makes a claim on [what is] mine and doesn’t know what I’d do with so much money” [Aber es auf einiger meiner guten Freunde vorkämet, als wenn er das Geld noch würklich in einer oder andern Handlung verstritt hatte, und mich vorsetzlich darum bringen wolle, unter dem nichtigen Vorstande. Er habe an dem meinigen noch eine Forderung, und wisse nicht was ich mit so vielem Gelde machen wolle] (ibid.).

Osterheide responded by reigniting a dispute over the estate of Wilhelm Süllow (d. 1730), Caspar Süllow’s eldest brother, whose assets had been unequally distributed among his four siblings. After receiving the lion’s share, Caspar “had his two brothers [Jobst Heinrich and Ernst Johann] make a declaration that he never again be subject to a claim about this inheritance from them and their heirs, and in which they renounce all favorable legal benefits” [einen Revers sich geben lassen dass er von Ihnen und Ihren Erben wegen dieser Erbschafft niemahls nicht solle wieder in Anspruch genommen werden, und worin sie sich aller Ihnen zu gute kommenden Rechtswohlthaten entsagen] (“Rechtskandidat Christian Johann Süllow” 7). Their sister, Osterheide’s mother, was excluded from this agreement and challenged the division of the estate in a German court, but could not bring Caspar Süllow to book while he resided in England. Osterheide now asserted that the money his cousin demanded was in fact his own birthright: “Since my mother did not consent and sign this declaration with her brothers, so I believe that my claim to this inheritance is evermore lawful and equitable” [als meine Mutter nicht mit Ihre Brüder in diesen Revers gewilliget und unterschrieben hat, so halte ich davon dass meine Forderung an diese Erbschafft allezeit rechtmässig und billig ist] (ibid.).

Following a inquiry into the administration of Wilhelm Süllow’s estate and Osterheide’s financial management of C.J. Sullow’s inheritance—which cataloged, among other things, the purchase of “a half share in the privateer named the Duke of Marlborough and a ticket in the Utrecht lottery, no. 10997″ [eine halbe Share in dem Privateer; the Duc of Marlboroug genannt, und ein Ticket in der utrechtschen Lotterie Nro. 10997] (“Rechtskandidat Christian Johann Süllow” 29)—the dispute was settled in Osterheide’s favor. “[I] wanted to report to Yr. Excellency most humbly that on last Saturday everything was settled between Mr. Süllow and me,” he wrote to Philipp Adolph von Münchhausen, head of the Deutsche Kanzlei, on 12 May 1760. “That is, I handed over all his documents and other things to Mr. Süllow, in return for which he gave me a full receipt for the accounts kept of my guardianship” [habe auf Eu: Excellentz gantz Unterthänigst berichten wollen dass am letzten Sonnabend zwischen H. Süllow und mir alles zur richtigkeit gekommen ist … ich habe nemlich an H. Süllow alle seine Schriften und sonstigten Sachen übergeben, dahergegen hat Er mir eine völlige Quitung über meiner geführte Vormundschaftlichen Rechnungen gegeben] (“Rechtskandidat Christian Johann Süllow” 42). C.J. Sullow addressed the same official more briefly that day “to offer the humblest thanks for the gracious and strong support in my case against my guardian and cousin” [Für dero gnädigen und kräftigen Beystand in meiner Sache gegen meinen Vormund und Vettern, den unterthänigste dank zu sagen] and hoping “the deep ingratitude toward my guardian” [dero hohe Ungnade gegen meinen Vormund] would be forgotten (“Rechtskandidat Christian Johann Süllow” 43, 44).

The question of what C.J. Sullow wanted with “so much money” (in addition to more books, as we shall see) is perhaps answered by the fact that on 21 July 1760 he married Johanna Augusta Sophia Hund⁴ of Woodstock, Oxfordshire, in his home parish of St. James, Westminster (“Marriage”). Sullow remained in London after his wedding and if not then employed in government service at least kept an eye on its doings.⁵ During the 1760s he took both The Court and City Kalendar (Verzeichniss 39) and the Siebenfacher Königlicher Gross-Britannisch- und Chur-Fürstlich Braunschweig-Lüneburgischer Staats-Calender (Verzeichniss 38) as well as the Hannoversches Magazin and Hannoversche Anzeigen, the papers of record for the Hanoverian civil service (Verzeichniss 8). In 1764 his public spirit drew him into a high-profile charitable endeavor: “Christian John Sullow, esq.” was one of “21 Gentlemen, of whom 7 to make a quorum,” chosen to constitute “a Committee … to manage the expenditure of the money subscribed for the relief of the poor Palatines &c.” (Proceedings iv). These were several hundred German emigrants recruited by ex-soldier Johann Christian Heinrich von Stümpel to found “Stümpelburgh” on land granted to him in Nova Scotia by the British Board of Trade. Stümpel brought them to England before “disappear[ing] with … the settlers’ money, leaving them without means to support themselves or to undertake their passage to the new world” (Selig 11-12). The Board of Trade “publish[ed] warrants for Stümpel’s arrest in various continental newspapers, which led to his apprehension in Ansbach in December 1764” but declined to aid the stranded migrants, who “remained on their ships … using up whatever provisions they had brought with them” with no prospect of relief (Selig 12). Fortunately their cause was taken up by Lutheran minister Gustav Anton Wachsel (ca. 1735-1799), first pastor of the largely German St. George’s Church in Whitechapel, who published an appeal for aid on 29 August 1764. He painted a horrifying picture of “men, women and children, about 600; consisting of Wurtzburghers and Palatines, all Protestants … perishing for food, and rotting in filth and nastiness” and prayed that God would “incline the hearts of the great and good of this kingdom, distinguished for its charity and hospitality, to take under their protection these their unhappy fellow Christians” (quoted in Proceedings ii-iii).

Donations began to pour in from every level of British society from King George III to “a widow woman of Whitechappel Parish, name unknown” (Proceedings [54]). The committee charged with their management, however, was drawn from a more limited circle. Chaired by M.P. Peregrine Cust (1723-1785), it was composed primarily of wealthy merchants, members of St. George’s Church, and government officials,⁶ among whom C.J. Sullow’s place in the pecking order is perhaps indicated by the fact that he was one of those carrying out the committee’s grunt work. On 6 September 1764, Sullow and two others were tasked with “pay[ing] the freight and charges of the Palatines on board of ship … also for clearing their baggage at the Custom-house” and “procur[ing] for the Committee an account of the exact number of the Palatines, distinguishing their age and sex, also their trades and professions, with the condition they are now in” (Proceedings v); two weeks later the committee directed Sullow and three others to provide “the following articles of cloathing for the Palatines … One spare shirt or shift for each person. One spare pair of shoes for each person above 10 years of age. One spare pair of thread stockings for each” (Proceedings ix). After the British government granted the emigrants land in South Carolina, the committee arranged their passage and on 12 October bade the first contingent farewell: “The Reverend Mr. Wachsel, Mr. Kirckmann,⁷ Mr. Sullow, Mr. Baden and the Secretary [William Lacey] who were appointed to go with the Palatines on ship board, reported that they saw and left them safe at anchor in the Downs, in good spirits and well satisfied” (Proceedings xx). No doubt Sullow’s ability to speak with the Palatines in their native tongue earned him this duty; he may also have been one of “the four German Gentlemen” instructed by the committee on 23 October to “see the remainder of the Palatines embarked with their baggage” (ibid.).⁸

Sullow’s bilingualism shaped his library, too: the second most common language of its texts after German was English. The 1796 auction catalog advertises folio editions of the collected works of Geoffrey Chaucer (1598; Verzeichniss 4) and Edmund Spenser (1611; Verzeichniss 5) and smaller editions of those of Alexander Pope (1751; Verzeichniss 21) and Jonathan Swift (1751; Verzeichniss 40) in addition to individual titles by Congreve, Cibber, Defoe, Milton, Richardson, Sterne, and others. Sullow owned Cervantes’ Don Quixote in two English translations, one by Thomas Shelton (1731; Verzeichniss 35) and the other by Peter Anthony Motteux (1749; Verzeichniss 39); he also acquired Tobias Smollet’s English rendition of Alain René Le Sage’s picaresque Gil Blas (1751; Verzeichniss 40). The catalog further records numerous English non-fiction works from Samuel Palmer’s General History of Printing (1733; Verzeichniss 11) and Giles Jacob’s New Law-Dictionary (1756; Verzeichniss 5) to Hannah Glasse’s Art of Cookery (1760; Verzeichniss 33) and Charles Thompson’s Rules for Bad Horsemen (1765; Verzeichniss 29). Sullow invested in copies of the eleventh edition of Thomas Dyche’s New General English Dictionary (1760; Verzeichniss 25) as well as the second abridged edition of Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (1760; ibid.) and evidently swore by John James Bachmair’s Neue Englische Grammatik, of which he owned at least four editions, two printed in London (1753 and 1758; Verzeichniss 28, 30) and two in Hamburg (1778 and 1789; Verzeichniss 31, 30). When making his purchases, Sullow may have patronized the shop of popular London bookseller Thomas Osborne (who also supplied English-language materials to the University of Göttingen); at the very least he took Osborne’s catalogs between 1760 and 1766 (Verzeichniss 38) and some titles in his library are also to be found among Osborne’s stock. On three occasions, for example, Osborne advertised the 1710 Edinburgh folio edition of Gawin Douglas’s translation of Virgil’s Aeneid—for 7/6 in 1761, 9/- in 1763, and 7/6 again in 1766—a copy of which eventually made its way onto Sullow’s shelves (Verzeichniss 4).

Other interests revealed by those shelves include gardening and forestry: Sullow acquired at least thirty titles on those subjects, most with imprint dates from the 1760s and early 1770s.⁹ Notable among them are the second edition of Carl Christoph Oettelt’s Practischer Beweis, Dass die Mathesis bey dem Forstwesen Unentbehrliche Dienste Thue (1765; Verzeichniss 20), William Hanbury’s Complete Body of Planting and Gardening (1773; Verzeichniss 5), and the 1737 edition of Adam Lonicer’s Vollständiges Kräuter-Buch (Verzeichniss 4). In 1774 Sullow took the post of Zollgegenschreiber [Comptroller of Tolls] in Hameln, Germany; there he and his wife Johanna baptized five children (Eckhardt 216) who left their own mark on his library with the addition of the third edition of Christian Felix Weisse’s Lieder für Kinder (1770; Verzeichniss 37), the anonymous Kindermoral in Bildern (1771; ibid.)¹⁰ and a 1775 German reprint of The Moral Miscellany, or, A Collection of Select Pieces in Prose and Verse for the Instruction and Entertainment of Youth, an anthology first issued by Ralph Griffiths in London almost two decades earlier (Verzeichniss 33). In later years Sullow developed a preoccupation with medicine; about half the titles on this topic in the 1796 auction catalog were printed between 1780 and 1795.¹¹ To household handbooks such as Gottwald Schuster’s Vernünfftige, Natur-mässige und in der Erfahrung Gegründete Methode, die Meisten Kranckheiten des Menschlichen Leibes Bald, Sicher und auf eine Angenehme Art zu heilen (1743-1744; Verzeichniss 9) and John Theobald’s hugely popular Every Man His Own Physician (1764; Verzeichniss 26) Sullow added more specialist works: textbooks like Christian Gottlieb Selle’s Medicina Clinica (1786; Verzeichniss 34) and Karl Gottfried Hagen’s Lehrbuch der Apothekerkunst (1786; Verzeichniss 21); journals such as Johann Friedrich Blumenbach’s Medicinisiche Bibliothek (Verzeichniss 24) and Christian Martin Koch’s Sammlung Auserlesener Abhandlungen zum Gebrauch für Praktische Aerzte (Verzeichniss 36); and treatises on particular topics like cancer—Zwey Specifische Mittel gegen den Krebs (1784; Verzeichniss 34) translated by Johann Gottfried Pfähler from two French works—eye disorders—Sammlung von Aufsätzen und Wahrnehmungen sowohl über die Fehler der Augen (1789; Verzeichniss 27), a translation of Guillaume Pellier de Quengsy’s Receueil de Mémoires et d’Observations tant sur les Maladies qui Attaquent l’Oeil—and venereal disease—Johann Friedrich Fritze’s Handbuch über die Venerischen Krankheiten (1790; Verzeichniss 29). Sullow also acquired editions of medical works printed in previous centuries, including Georg Pictorius’s De Tuenda Sanitate Tractatus VII (1549; Verzeichniss 40), George Wateson’s Rich Storehouse, or Treasurie for the Diseased (1630; Verzeichniss 12), De Proprietatibus ac Virtutibus Medicis Animalium, Plantarum, ac Gemmarum, Abraham Ecchellensis’s translation of Suyūṭī’s Dīwān al-hayawān (1647; Verzeichniss 33), and the Schola Salernitana attributed to Joannes de Mediolano (1667; Verzeichniss 40). Unfortunately no amount of medical knowledge could prevent Sullow from going the way of all flesh in the mid-1790s; he was buried on 7 January 1796 in Hameln (Eckhardt 216) and his library was “on [a certain day in] April 1796, and the following days in the morning and afternoon at the usual hours in the home of the deceased publically sold to the highest bidders” [am [blank] April 1796, und folgenden Tagen Morgens und Nachmittags an den gewöhnlichen Stunden in der Wohnung des verstorbenen den Meistbietenden öffentlich verkauft] (Verzeichniss 1).

De Perenni Philosophia Libri X was not among the books offered for sale; it is not clear how this volume passed to its next named owner, Ernst Anton Heiliger (1729-1803), whose ex-libris appears with some handwritten notes on Sullow’s bookplate (see images above). A native of Hannover, “where his father was overseer of the royal funds” [wo sein Vater Aufseher über die königlichen Gelder war], Heiliger earned a doctorate in civil and canon law from the University of Göttingen in 1751 (Rotermund 295). In 1753 he began a fifty-year career in Hanover’s ecclesiastical and secular government, serving variously as Konsistorialrat [consistorial councillor], syndic, mayor of Hanover and Hofrat [court councillor]. A man of “great literary erudition and extraordinary knowledge of local history” [grosse literarische Gelehrsamkeit und ausserordentliche Kunde der Landesgeschichte], Heiliger also amassed “a truly remarkable collection of books, which contained many rarities” [eine in der That merkwürdige Bücher-Sammlung, die manche Seltenheiten enthielt] over the course of his life (ibid.). Among them was Kislak’s copy of De Perenni Philosophia, which the note accompanying his ex-libris characterizes as “liber rarus” [rare book] with reference to Johann Vogt‘s Catalogus Historico-Criticus Librorum Rariorum (first published 1732) and Johann Georg Schelhorn‘s Amoenitates Literariae (first published 1724-1731). In addition to curating his own collection, Heiliger continued the efforts of his mayoral predecessor, Christian Ulrich Grupen (1692-1767), to modernize Hanover’s Ratsbibliothek [council library]; Marion Beaujean, former director of the Stadtbibliothek Hannover, opines that Grupen and Heiliger “laid the foundation for the later development of the modern Stadtbibliothek through their work” [durch ihre Arbeit den Grundstock für die spätere Entwicklung zur modernen Stadtbibliothek gelegt haben] (227). After leaving Heiliger’s possession his liber rarus found a place on the shelf of another Hanoverian bureaucrat who signed himself “C. Fr. W. Fricke.” Christian Friedrich Wilhelm Fricke (1774-1830) entered public service as a registrar for the Geheime Kanzlei [privy council] in 1818 and the following year began working in Hanover’s Intelligenz-Comtoir [information office], eventually becoming editor and proofreader of its publications (Vogel 114, note 2). Another of Fricke’s books, a 1707 edition of Strabo’s Geōgraphiká printed by Joannes Wolters of Amsterdam, is currently held by the Moravská Zemská Knihovna in Brno, Czech Republic. In addition to Fricke’s autograph it contains that of classicist Karl Friedrich Hermann (1804-1855) dated July 1830, suggesting that at least some of Fricke’s books were dispersed on his death.

The final mark of provenance in the Kislak copy of De Perenni Philosophia is a Mundelein College Library bookplate identifying this volume as the gift of John Rothensteiner. Named for George William Cardinal Mundelein, Archbishop of Chicago (1872-1939), Mundelein College was a Roman Catholic women’s college founded and run by the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary (BVM) in Chicago, Illinois, from 1929 to 1991, when it was incorporated into Loyola University Chicago. Sister Mary Justitia Coffey (1875-1947), Mundelein’s ambitious and astute first president, determined that “the new library … needed a collection of at least ten thousand volumes by opening day” and encouraged donations towards this goal both in money and in kind (DeCock 16). Through the offices of another BVM sister, Mary Callista Campion (1891-1957), then a graduate student in history at the University of Illinois and later a teacher at Mundelein, a “dramatic response to this request came from the Rev. John Rothensteiner of St. Louis … [who] sent two thousand books within the first year and eventually bequeathed his entire twenty-thousand-volume library, which became the heart of Mundelein’s rare-book collection” (ibid.).

Born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1860, John Ernest Rothensteiner was the middle child and eldest son of immigrants John Rothensteiner (d. 1896), a tailor, and his wife Maria Magdalena (née Pott; d. 1915). Rothensteiner studied for the Roman Catholic priesthood at St. Francis Seminary in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and was ordained in 1884. From 1887 to 1907 he served as pastor of St. Michael parish in Fredericktown, Missouri, and from 1907 until his death in 1936 as pastor of Holy Ghost parish in St. Louis. Lauded as “a model pastor and successful administrator as well as poet … author and historian” (Bachhuber 21), Rothensteiner led a busy life of service and scholarship. He spearheaded significant capital improvements at his parishes: at St. Michael he oversaw renovations to the church, among them the installation of a new organ and a full ring of bells; at Holy Ghost he superintended the building of a new church, rectory and school. Fluent in German and English, Rothensteiner preached in both languages and translated German hymns into “the more congenial form of English verse” for the use of an Americanizing Catholic population (quoted in Bachhuber 22). Later in life he turned to translating secular German poetry, releasing two well-received anthologies, The Azure Flower (1930) and A German Garden of the Heart (1934), the latter praised as “the most representative collection of German lyrics in English translation that we have” (Bruns 25). Although he published several books of original poetry in both his native languages, Rothensteiner saw the “practice of writing verse, which has haunted me throughout the greater part of my life” as a hobby, if “a most pleasant one … tending to keep the heart ever young and buoyant and free” (Rothensteiner, Chronicles 46). Notable in his prose bibliography are two book-length studies: Die Literarische Wirksamkeit der Deutschen-Amerikanischen Katholiken (1922), a survey of German-American Catholic literature, and a two-volume History of the Archdiocese of St. Louis in its Various Stages of Development from A.D. 1673 TO A.D. 1928 (1928), “the first general account of the origin and development of the [Catholic] Church in the Mississippi Valley” that ensured Rothensteiner lasting recognition as a historian (Bachhuber 35). He was also a leader in local ecclesiastical and secular historical organizations: charter member, secretary and archivist of the Catholic Historical Society of St. Louis; associate editor of as well as contributor to its journal, the short-lived St. Louis Catholic Historical Review (1918-1923); and long-serving trustee of the State Historical Society of Missouri.

Like his poetry, Rothensteiner described his library as the product of an idle avocation: “Money that might have been spent for luxuries has been used by me to indulge this little hobby of mine” (quoted in Bachhuber 38). His friend and fellow scholar Friedrich Bruns begged to differ—”Books would arrive when the housekeeper wanted and needed new curtains and table linen” (25)—and not even Rothensteiner could deny that his “little hobby” left a large footprint. A boxcar was required to move his books from Fredericktown to St. Louis in 1907; a journalist who interviewed him in 1931 observed in Rothensteiner’s study and attic “[s]helves full of books. Racks full of books. And here and there yawning spaces which … were until only recently filled by choice volumes that now repose in other libraries” (quoted in Bachhuber 38). His acquisitions were only partly driven by the scholarly necessities of the pre-Information Age; more than “the library of the theologian and church historian” Bruns envied Rothensteiner “the library of a cultivated man of letters … There were standard editions, often rare and valuable first editions of the chief English and German poets. There were Piers the Plowman, Chaucer, and Shakespeare. There were Goethe and the Romanticists and a fine collection of the Middle High German poets” (25). Rothensteiner was clearly a bibliophile, though he might have rejected the term judging by the way he sent it up in a poem by that title. “Peruse my books! No, no, I love my friends / Too dearly, Sir, for such ignoble use,” his narrator proclaims, preferring “To gaze upon them with approving eye, / And show them to my visitors, and dwell / Upon their age and rarity and price” but “never read / Save title-page and colophon” (Rothensteiner, Heliotrope 39). Rothensteiner, by contrast, bought books to read and to share with other readers. “I have never attempted to gather first editions, because this is something only the rich can enjoy,” he told his 1931 interviewer, “but during my browsings around I have come upon some of these, too, and I have them now—if I haven’t given them away” (quoted in Bachhuber 38).

After his initial gift to Mundelein, Rothensteiner donated a further ten thousand volumes to the college over the next six years and left it as many again on his death in 1936 (Bachhuber 38). Among them were volumes ranging from fifteenth-century incunables—such as Johannes Amerbach’s printing of the works of Saint Anselm (1497) and a volume of Giovanni Britannico’s commentary on Statius’s Achilleid (1485) bound with Sidonius Apollinaris’s letters and panegyrics (1498)—to twentieth-century limited editions—such as the Abbey Shakespeare Merry Wives of Windsor (1902) and Romeo and Juliet (1902) and the Roycroft Press As You Like It (1903) and King Lear (1904)—covering a wide range of theological, historical and literary topics in both classical and modern European languages. Including, of course, a copy of Agostino Steuco’s De Perenni Philosophia Libri X from the sixteenth-century Swiss press of Nikolas Brylinger and Sebastian Franck. Has it finally found its forever home in the stacks of the Kislak Center at the University of Pennsylvania after four hundred and seventy-nine years and at least six changes of ownership? Only time, as Brylinger’s lions might observe, will tell.

Notes

¹ Dr. Burr (incidentally this blogger’s distant cousin) may well have been the Penn Libraries’ most bountiful twentieth-century patron: “It is not clear how many titles Burr donated to the Library, but the number could well approach 25,000. In 1932 alone he contributed 19,000 volumes to the collections. Burr’s major interest as a collector was Aristotle and the Aristotelian tradition in the West. Thanks to him, the Penn Library has what must be the largest collection in the country on Aristotle and his legacy” (Ryan 25).

² Bauer, a theology student, came to Helmstedt from Göttingen, mirroring Sullow’s curriculum vitae; he subsequently served as pastor of Dassensen and Drakenburg (Funke and Fricke 06.5). Their paean to the power of love begins:

O Liebe! deinen Zärtlichkeiten,

Wenn sie ein fühlend Herz bestreiten,

Bleibt das besiegte Herz zu schwach.

Dein holder Zug belebt, o Liebe,

Auch ein kummervolle Brust.

Die Wehmut selbst verlernt das Trübe,

Wird heiter, scherzt, und fühlet Lust.

[O love! If your caresses deny a feeling heart, the conquered heart remains too weak. Your lovely train, o love, also enlivens a sorrowful breast. Melancholy itself forgets the gloom, becomes cheerful, jokes, and feels pleasure.] (Fritzsche 81)

³ Johann Wilhelm Jansen of Lüneburg, a medical student, matriculated at Helmstedt on 3 May 1756 and at Göttingen on 14 May 1757 (Mundhenke 212; Richter 64). “S.J.S. Schul(t)ze” is an error for Johann Samuel Jacob Schulze of Braunschweig, a medical student who matriculated at Helmstedt on 16 June 1753 and at Göttingen on 15 May 1757 (Mundhenke 206; Richter 64).

⁴ Caroline Eckhardt gives Sullow’s spouse’s name as “Johanne Charlotte Henriette Hund” (216). The marriage was witnessed by Hanoverian-born George John Frederick [Georg Johann Friedrich] Schönian (b. 1733) and John Benefold, Jr. (d. 1793), the parish clerk.

⁵ I have found no evidence of where Sullow was employed prior to his appointment as Zollgegenschreiber (Comptroller of Tolls) in Hameln, Germany, from 1774-1795 (Eckhardt 216).

⁶ Some individuals feature in more than one category; for the identities and affiliations of most members of the committee, see Selig 13, note 34. To his list of known participants I can add C.J. Sullow; Caribbean sugar plantation owner and slave trader Gidney (Gedney) Clarke, Jr. (1735-1777); and possibly Secretary of the Post Office Anthony Todd (1717-1798).

⁷ Possibly to be identified with either Jacob Kirkman (1710-1792) or his nephew Abraham Kirkman (1737-1794), immigrants from Alsace and harpsichord makers.

⁸ Some three-quarters of the Palatine emigrants survived their journey to South Carolina, where they were settled in the northwestern portion of the state. Their community, named Londonderry in honor of their British benefactors, endured about forty years before coming to naught (Selig 19ff).

⁹ Sullow also participated at least once in the 18th-century fad for picturesque tourism: in 1766 he ascended the Brocken, a popular North German destination, and on 24 June signed its Jahrbuch. The autograph is recorded as “C.B. Süllow, aus London” (Jahrbücher 87), but “B” is almost certainly a misprint or misreading of “J”.

¹⁰ Sullow does not seem to have shared the opinion of a contemporary reviewer who criticized Kindermoral in Bildern as “a very insignificant contribution to the education of youth” [Ein sehr unbedeutender Beitrag zur Bildung der Jugend] with “bad woodcuts” [Schlechte Holzschnitte] and moral lessons “mostly quite irrelevant and extremely forced” [meistens ganz unerheblich und überaus erzwungen] (“Kindermoral in Bildern”). Or, if he did, it was insufficient motivation to banish the book from his library.

¹¹ They also comprise about forty percent of all the books in Sullow’s library printed between 1780 and 1795, a signifcant investment on a single topic. Horticultural books, by contrast, make up not even twenty percent of the 1760-1779 imprints.

Works Cited

“Albumtulajdonos: Perlaki, Gábor. Bejegyző: Sullow, Christian John.” Inscriptiones Alborum Amicorum, Szegedi Tudományegyetem, iaa.bibl.u-szeged.hu/index.php?page=browse&entry_id=2884 . Accessed 13 February 2021.

Bachhuber, Claire Marie. The German-Catholic Elite: Contributions of a Catholic Intellectual and Cultural Elite of German-American Background in Early Twentieth-Century Saint Louis. 1984. Saint Louis University, PhD thesis.

Beaujean, Marion. “Die Bibliotheca Senatus Hanoverensis im Zeitalter der Reformation.” Beiträge zur Geschichte des Buchwesens im konfessioneller Zeitalter. Edited by Herbert G. Göpfert et al. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1985. 213-228.

Bruns, Friedrich. “John Rothensteiner.” The American-German Review 4.4 (1938): 24-25.

“[Death and burial of Caspar Süllow, 15/19 February 1749/50].” England & Wales, Non-Conformist and Non-Parochial Registers, 1567-1936, Ancestry.com, 2013, tinyurl.com/y6bcrxp7 . Accessed 3 December 2020.

DeCock, Mary. “Creating a College: The Foundation of Mundelein, 1921-1931.” Mundelein Voices: The Women’s College Experience, 1930-1991. Edited by Ann M. Harrington and Prudence Moylan. Chicago: Loyola Press, 2001. 3-29.

Eckhardt, Caroline D. “The Manuscript of Castleford’s Chronicle: Its History and Its Scribes.” The Prose “Brut” and Other Late Medieval Chronicles. York: York Medieval Press, 2016. 199-217.

Fritzsche, R.A. “Über Gelegenheitsgedichte: Ein Vortrag.” Mitteilungen des Oberhessischen Geschichtsvereins 13 (1905): 80-100.

Funke, Hans, and Gabriele Fricke. Die Pastoren von Luthe. (In den Kirchenbüchern beginnen T 1639, Tr 1639, B 1640). Wunstorf.de, tinyurl.com/wq01y86i . Accessed 4 February 2020.

Grebe, Anja. “Ein Gebetbuch aus Nürnberg im Germanischen Nationalmuseum und das Frühwerk von Nikolaus Glockendon.” Anzeiger des Germanisches Nationalmuseums (2005): 97-120.

Hardtwig, Wolfgang. “Studentenschaft und Aufklärung: Landsmannschaften und Studentenorden in Deutschland im 18. Jahrhundert.” Sociabilité et Société Bourgeoise en France, en Allemagne et en Suisse, 1750-1850. Ed. Etienne François. Paris: Editions Recherche sur les Civilisations, 1986. 239-259.

Hayn, Hugo. Bibliotheca Germanorum Erotica. 2. Aufl. Leipzig: Albert Unflad, 1885.

“[Heirat, Caspar Sullo mit Ilsa Catharina Mehlbaums].” Bremen, Germany and Hannover, Prussia, Germany, Lutheran Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, 1574-1945, Ancestry.com, 2011, tinyurl.com/ybu7ts2l . Accessed 3 December 2020.

Jahrbücher des Brockens von 1753 bis 1790. Magdeburg: Johann Adam Creutz, 1791.

Kagel, Martin. “Brothers or Others: Male Friendship in Eighteenth-Century Germany.” Colloquia Germanica 40.3/4 (2007): 213-235.

“Kindermoral in Bildern. Berlin, 1771, bey Winter, 4 Bogen kl. 4.” Allgemeine Deutsche Bibliothek 24.1 (1775): 79.

“[Marriage of Christian John Sullow and Johanna Augusta Sophia Hund].” Westminster, London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1935, Ancestry.com, 2020, tinyurl.com/yyurgyaf . Accessed 22 January 2021.

Mundhenke, Herbert, ed. Die Matrikel der Universität Helmstedt, 1685-1710. Hildesheim: Verlag August Lax, 1979.

“Predatory Behaviour.” ALERT, Lionalert.org, 8 January 2020, lionalert.org/predatory-behaviour/ . Accessed 1 December 2020.

Proceedings of the Committee Appointed for Relieving the Poor Germans, Who Were Brought to London and There Left Destitute in the Month of August 1764. London: J. Haberkorn, 1765.

“Rechtskandidat Christian Johann Süllow, Sohn des weiland Kriegskanzlisten Süllow zu London, wider seinen Vormund, den Pedellen Wilhelm Osterheyde zu London, wegen der von diesem abzulegenden vormundschaftlichen Rechnung.” Arcinsys Niedersachsen and Bremen, NLA Hannover Hann. 92 Nr. 40, 1760, arcinsys.niedersachsen.de/arcinsys/detailAction?detailid=v3353012 . Accessed 10 December 2020.

Richter, Walter. “Akademische Orden in Helmstedt.” Braunschweigisches Jahrbuch 57 (1976): 49-92.

Richter-Uhlig, Uta. Hof und Politik unter den Bedingungen der Personalunion zwischen Hannover und England. Hannover: Hahn, 1992.

Rotermund, Heinrich Wilhelm. Das gelehrte Hannover. Bd. 2. Bremen: Carl Schünemann, 1823.

Rothensteiner, John E. Chronicles of an Old Missouri Parish: Historical Sketches of St. Michael’s Church, Fredericktown, Madison County, Mo. St. Louis: “Amerika” Print, 1917.

—. Heliotrope: A Book of Verse. St. Louis: B. Herder, 1908.

Ryan, Michael T. “A Library in Retrospect.” The Penn Library Collections at 250. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Library, 2000. 9-32.

Selig, Robert A. “Emigration, Fraud, Humanitarianism, and the Founding of Londonderry, South Carolina, 1763-1765.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 23.1 (1989): 1-23.

Stewart, Gordon M. “British Students at the University of Göttingen in the Eighteenth Century.” German Life and Letters 33.1 (1979): 24-41.

Verzeichniss des von Wayland Zollgegenschreibers Süllow in Hameln Nachgelassenen Vorraths von Meistens Deutschen und Englischen Büchern, aus Allen Theilen der Wissenschaften. Pyrmont: Herrnkinds Schriften, 1796.

Vogel, Walter, ed. Briefe Johann Carl Bertram Stüves. Bd. 1. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1959.